Chapbook — A link to the North East’s Folk Music History

RUTH SALTER shares the story of Chapbook

RUTH SALTER shares the story of Chapbook

Some of the very first words of Scotland’s mid-twentieth century Folk Revival commended the folk music of Aberdeenshire: speaking in Edinburgh in 1951 the folklorist Hamish Henderson ushered in the revival movement while praising the ‘fine rumbustious quality’ of Buchan folksongs. ¹ The North East had long held a significant position in the history of Scottish folk music, and with the development of the Revival over the following two decades the area’s stature as a centre of folksong would become even more renowned.

I am a PhD student researching the Revival in Scotland. I have a dual purpose in mind in writing this article: to share with you a little of Aberdeen’s musical history, especially as it relates to the Revival movement; and to seek out anybody who may have old copies of Chapbook, the Revival magazine of Aberdeen Folksong Club, who might be able to help me with my research. First, let me sing for my supper.

A reputation for folksong

The North East’s reputation for folksong dates back at least several centuries. Danny Couper, fish merchant and co-founder of Aberdeen Folk Club, explains this history through the area’s links with fishing and farming. ² Fishing communities all over Scotland have traditions of song and choir; more local to Aberdeen are the Bothy Ballads, written and sung by North East farm workers and named for the basic farm buildings in which they lived. Aberdeenshire was also home to many Travellers who took part in an active oral culture which included singing and storytelling.

The area’s strong links to ongoing musical traditions attracted people interested in folksongs and ballads for many years before the Revival: 91 of Francis James Child’s seminal collection of 305 ballads, from the second part of the nineteenth century, are from Aberdeenshire; ³ while Gavin Grieg and James Bruce Duncan’s revered collection, from the start of the twentieth century, includes nearly two-thousands songs recorded in the North East.

All ears turned to the North East

Unsurprisingly, then, when the Scottish Folk Revival of the mid-twentieth century got underway all ears turned once again to the North East. The Revival was a far-reaching movement to re-introduce the people of Scotland to a style of folk music which many, especially in urban central-belt areas, knew little about. Spanning the 1950s and 60s, the Revival had different intentions for different people: to ‘save’ what was seen by some as a dying culture; to regenerate that culture and give it a renewed vitality; to show that the everyday culture and experiences of normal people were worthwhile, meaningful and powerful; and to address political issues through this form of popular culture. With so many aims, the movement also spanned a range of activities.

In its first decade, the 1950s, a lot of the Revival centred around finding and recording folksong singers. The largest amount of so-called ‘collecting’ was carried out by workers from the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh. Folklorists from the institution, such as Calum MacLean and Hamish Henderson, utilised new portable technology to visit and record singers, storytellers, and other people who took part in traditional culture all over Scotland. Many people who collectors revered for their knowledge of folksong were from the North East, including Jessie Murray, Jimmy MacBeath and Jeannie Robertson — all singers who many involved in Scottish folk music nowadays would still think of very highly.

Aberdeen Folksong club

By the turn of the decade, the collecting-focus of the early years was giving way to growing public interest in folksong. In the early 1950s, a series of ceilidhs had been organised in Edinburgh as part of the People’s Festival, designed ‘By Working People for Working People.’ ⁴ These introduced people to folk music, demonstrated that the tradition had not yet disappeared, and set some on their own path to folk revivalism. From the late 1950s through to the end of the Revival, a growth of public-facing activities introduced new audiences to longstanding folksingers and generated a huge uptake in folk singing among fresh enthusiasts. Commercial records were published, print and broadcasting media gave increasing time to folk music, and across the country folk clubs and festivals were founded.

Aberdeen Folksong Club was founded in 1962 by Danny Couper, introduced above, and Arthur Argo, a journalist and great-grandson of the previously-mentioned collector Gavin Greig. Most folk club meetings in this period followed a similar set-up: an invited guest would perform several times across an evening, and the rest of the night would consist of ‘floor spots’ where club members and the audience could contribute. Where Aberdeen Folksong Club differed was in the ongoing vitality of the musical culture which surrounded it.

While clubs elsewhere in Scotland might have to look around the country for guests, singers local to Aberdeen were also some of the hallowed names of the Revival. Well-grounded as it was in the region’s traditional music, though, the Club could also draw in larger acts; Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger, Jean Ritchie, and Martin Carthy all topped the bill at Club nights or festivals within a few years of its opening. Couper explains how, for Argo, Northeast songs were part of a ‘global context’; 5for many involved in the Revival, at Aberdeen Folksong Club and elsewhere, folk music spoke to the international experiences of working people.

The revival and Chapbook

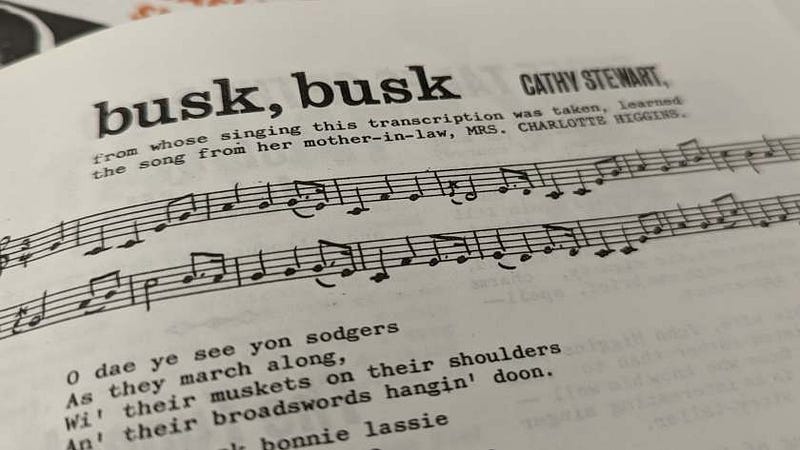

Aside from live performances, Aberdeen Folksong Club also played another major role in the Revival: the Club magazine Chapbook, published from 1964 to 1969, became the de facto publication of the Scottish movement. The magazine was edited by Argo, initially in Aberdeen and later from Edinburgh, and Ian Philip and Carl MacDougall, who brought perspectives from the West of Scotland. Chapbook took its name from small, cheap paper booklets sold as street literature mostly throughout the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries.

The magazine, which regularly ran to over 30 pages, contained matters relevant to both the Aberdeen and national folk scene: new and old songs, notices and reviews of events and records, and discussions on topics ranging from the state of Scottish folk clubs to William McGonagall’s relationship with ‘folk-poetry’. Some magazines also contained more miscellaneous content, like cartoons of prominent folkies or instructions for homebrewing beer!

As I mentioned at the start of this article I am researching the Folk Revival in Scotland and, given the forefront position of Chapbook within the movement, very keen to study as many copies of the magazine as I can. My research looks especially at the Revival’s cultural-political position and, as part of this, I’m interested in how people took part in, viewed, and talked about folk music during the period. Chapbook offers a great window into the Revival, demonstrating what the people running and attending folk clubs felt should be shared with the national movement. Some copies of the magazine are available through libraries in Edinburgh, but the collections are far from complete and aren’t the most accessible to me at present.

Can you help in finding copies of Chapbook

I would therefore love to hear from anybody who might have an old copy or two tucked away that they would be willing to let me look at (for my purposes a photocopy would suit just as well as the real thing!). If you might be able to help please contact me via email at ruth.salter@ed.ac.uk.

Although the focus of this article has been historical Aberdeen Folk Club is, of course, not a thing of the past. The Club, which has long since dropped ‘song’ from its title to reflect the post-revival growth of instrumental folk music, still meets regularly. The group can be found every Wednesday at the Blue Lamp, 121 Gallowgate, beginning from 8 pm for an 8.30 pm start. Singers, instrumentalists and listeners are all welcome for sessions and open mic nights, and the Club also hosts occasional concerts from visiting artists. Aberdeen Folk Club just celebrated their 60th birthday and are still one of the top clubs going, winning Club of the Year at the most recent Scots Trad Music Awards. The prize is demonstrative that that ‘fine’ folk song Henderson identified in the North East in the 1950s still has a home in Aberdeen.

Footnotes

1 This event was the first Edinburgh People’s Festival Ceilidh, which I discuss more below. A recording of Henderson speaking these words can be found at the Lomax Digital Archive.

2 Quoted in Ewan McVicar, The E****o Republic: Scots political folk song in action 1951 to 1999 (Linlithgow: Gallus Publishing, 2010), p. 137

3 Les Wheeler, ‘ Traditional Ballads in North East Scotland ‘

4 Hamish Henderson, ‘The Edinburgh People’s Festival, 1951–54' in A Weapon in the Struggle: The Cultural History of the Communist Party of Great Britain, ed. by Andy Croft (London; Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press, 1998), pp. 163–170 (p. 165)

5 Quoted in McVicar, p. 261